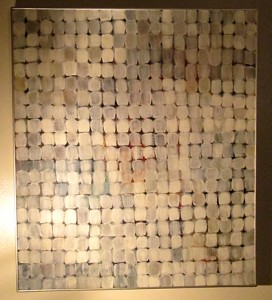

The oil painting above my piano reminds me of lessons I too easily forget. Row upon row, the gray brush strokes, roughly an inch square, contain subtle elements of color. The color comes from a painting I wanted to paint—and attempted to. But the painting came from learning to let go of ideal notions that constrained me so I could allow experience to inspire something better.

The oil painting above my piano reminds me of lessons I too easily forget. Row upon row, the gray brush strokes, roughly an inch square, contain subtle elements of color. The color comes from a painting I wanted to paint—and attempted to. But the painting came from learning to let go of ideal notions that constrained me so I could allow experience to inspire something better.

Long, long ago, at a liberal arts college far, far away, a class of earnest, would-be artists, took a painting course to develop what they hoped might be talent. They discovered that painting entailed more than standing at the easel wearing a beret. They learned about color and line and to notice what wasn’t there as well as what was. They filled sketch books to practice the art of seeing their world beyond the obvious.

I still notice the interesting shapes between the balusters of the stairways I climb. I see the defining darkness around a lighted object at night because I was, of course, one of those eager students. In the course of my sketching one day, I became enamored with a little abstract drawing on one page. I determined to translate its fascinating triangular elements into a full-size painting. So I headed to the college art studio and began.

Once on canvas, however, it no longer appeared so brilliant. It sat there, unresponsive, while I adjusted this line and that one, this color and that. My professor encouraged me to respond to what I saw on the canvas rather than what I “saw” in my head with limited effect. Eventually, I focused on a lovely middle horizon of color. But nothing would bring the top or the bottom into harmony with that marvelous middle.

Finally, I gave up and decided to paint over everything except the middle masterpiece. I grabbed my largest brush, swabbed up a load of white paint, and began to daub determinedly at the canvas, starting at the top. The oil paint beneath it remained wet. Each stroke of white picked up those underlying colors. This created subtle grays, whites, and colors within each brush stroke. It fascinated me. I began to place each brush stroke regularly, attempting to recreate the effect. I decided that instead of just painting an even, flat color above and below the middle, I would preserve those brush strokes for their particular interest. Now I envisioned a tripartite painting. A textured gray field on top and bottom would offset the loud reds and oranges of the center section.

I finished. The painting still did not work. I compromised. I daubed over one more area. I compromised again. Each time, I made a selection and preserved one compelling area at the expense of another. Finally I surrendered the dearest center, obscuring every bit of my original. I let the paint have its way and erase all the plans and prejudices in my head. My sketch was gone. But a painting with some integrity, amateur though it was, sat before me.

I still try to make my sketches work. I create a plan—for an event, an interaction, or project. I treat life like that old canvas, hoping to force it to manifest my brilliance. In youth, I could push, pull and twist things to an approximation of what I had envisioned. I no longer possess such unlimited energy. More and more, I must let go of the sketch. Then I can respond to the subtleties happening before my eyes, capture their beauty, and let life’s painting become what it will.